An SRE's Guide to Distributed Consensus, Part 1

This is the first of three posts on distributed consensus in the DevOps world. These posts are based on a presentation I gave to the Nairobi GNU/Linux Users Group. A video of the presentation can be found here.

Consensus is when a group of individuals comes to an agreement, or a general agreement. A general agreement implies that not all individuals in the group need to agree with the decision. As long as most of the individuals have agreed then we can assume that a general consensus was achieved.

Consensus in Computing

There are several applications for consensus in computing. As an example, if you have several workers that can process queued tasks, the workers will need to reach a consensus on which of them should process a task in the queue to prevent situations where more than one worker processes the same task. This can be achieved by assigning a lock to each task on the queue. The workers then agreed that whichever worker acquires a task’s lock first will be responsible for processing that task.

Consensus in synchronized systems, like the one I have just mentioned, is more often than not, a trivial problem and can be achieved using locks (which are also called mutexes) and semaphores.

However, consensus in distributed systems is a non-trivial problem due to the nature of distributed systems. Distributed systems are generally assumed to contain independent components (which I’ll call nodes) that are connected to each other over the network. It is expected that both the nodes and the network connecting the nodes are prone to failure.

Distributed Consensus

The big consensus problem in distributed systems then is; “How to achieve consensus when some of the nodes that are expected to agree on something aren’t all reachable at the same time but are likely to be reachable at some point in time”.

Because consensus in distributed systems is not a trivial problem to solve, several algorithms have been created to tackle it. Most of these algorithms assume that nodes in a distributed system may fail temporarily or permanently. They also assume that the network connecting the nodes can have varying latencies and that there is a possibility of network partitions (this is where different sections in a network are unable to reach each other for some time).

The algorithms also assume that nodes in a distributed system might have varying computing power and varying system clocks. You, for example, can have two nodes, A and B, in a distributed system where A is a beefy server and B is a not-so-beefy laptop. A’s system clock might be synchronized with an NTP server and B’s system clock might not be synchronized with anything at all, and therefore is likely not be accurate.

“What example distributed consensus algorithms exist?”, you may ask. Before I answer this question, I’ll tell a short story that hopefully will explain a bit why the distributes consensus landscape is what it is today. In 1984, Leslie Lamport (some of us might know him as the the initial developer of LaTeX), in a paper titled “Using Time Instead of Timeout for Fault-Tolerant Distributed Systems”, defined an approach of solving the distributed consensus problem which he called the state machine replication approach.

I’ll try expound a bit more on what state machines are and what state machine replication entails. Let me first finish the short story.

In 1989, Lamport came up with the Paxos protocol for distributed consensus. Paxos relies on the state machine replication approach he had presented in 1984. It turns out that several of the most popular distributed consensus algorithms today fall under the Paxos family and maintain some aspects of the original protocol. It’s also important for me to state that several other popular, non-Paxos, distributed consensus algorithms also follow the state machine replication approach.

Fun fact: Paxos is named after the Greek island Paxos. This isn’t random really. Lamport, in his 1984 paper, explained the state machine replication approach using an analogy of a fictitious parliament on the island of Paxos that had to function “even though legislators continually wandered in and out of the parliamentary Chamber”.

State Machines

So… What is a state machine? A state machine is something which when fed a command, changes from one discrete state to another. A good example of a state machine is a database, which if you feed a query, might change from one state to another.

If you, for instance, run an insert query against a database, the database will change from a state where it didn’t have the data inserted using the query to a state where it has this data. In this example, the database is the state machine, and the insert query is a command that changes the database from one state to another.

Another example of a state machine is a video game. When you feed a video game commands through an input device, like a game pad, the video game changes from a state where, for instance, a character is standing to a state where the character is seated.

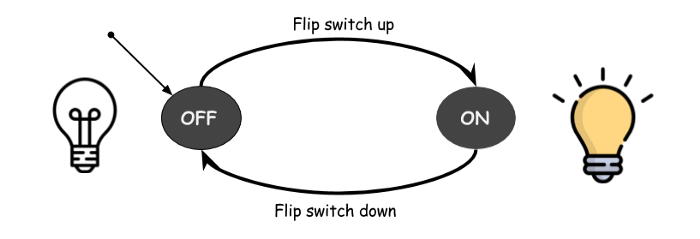

A simpler example of a state machine is a light bulb. When you flip the light bulb’s switch up, the bulb transitions from a state where it was off to a state where it is on. When you flip the switch down, the light bulb transitions from a state where it was on to a state where it is off. The act of flipping the switch up or down is the command, in this example and the light bulb (who’s state is affected by commands applied on it) is the state machine.

The image above is what is called a state machine diagram. It’s used to show the different discrete states a state machine can be in as circles. The directional lines connecting the circles represent the commands that transition the state machine from one of its discrete states to another.

An important characteristic of state machines is, if you feed the machine a sequence of commands, you will always end up in the same state if the number and order of commands is maintained. State machine replication involves sharing commands (intended to be applied to state machines) in a manner that preserves the number and order of these commands. The assumption is that if, for instance, commands are shared amongst 10 individuals, each in possession of the same kind of state machine, after each of the individuals has applied the shared commands on their state machines, all the state machines will be in the exact same state.

In the state machine replication approach, consensus is achieved when a majority of the nodes agree on the commands to apply against their individual state machines and in what order these commands should be applied.

In the next post, I will talk about Raft, and how it handles distributed consensus.