An SRE's Guide to Distributed Consensus, Part 2

This is the second of three posts on distributed consensus in the DevOps world. These posts are based on a presentation I gave to the Nairobi GNU/Linux Users Group. A video of the presentation can be found here.

The first post in this series introduced distributed consensus. I’ll introduce the Raft consensus algorithm in this post and try to explain how it handles distributed consensus.

The Raft algorithm is broken down into three parts. The first part is leader election where the nodes in a cluster elect one of them to be their leader. The second part is log replication which handles how commands are gotten from the clients, sent to the nodes in the distributed system, and finally safely applied to their state machines. The third part (called safety) deals with how to handle certain edge cases during leader election and log replication. Don’t worry. The role of the leader in Raft will become clear when I explain how log replication works.

For the purposes of this post, I will only focus on explaining a bit of how leader election and log replication work in Raft. I will, however, not cover anything on safety. I highly encourage you to visit this site for a visual explanation of how Raft handles leader election, log replication, and safety.

Leader Election

In the last section, I explained the architecture of a distributed system in Raft where each of the nodes is expected to have a log and a state machine. Apart from each node having a log and a state machine, they also have an integer counter called a term. This counter is what is used to distinguish a past leader from a current leader. Each of the nodes have the initial value of their term set to 1.

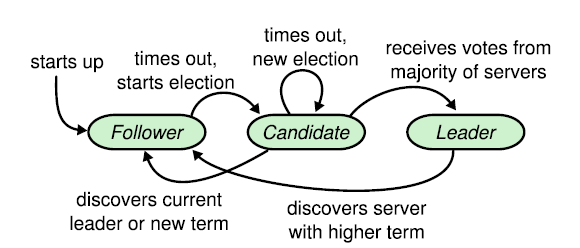

Nodes in the cluster can be in one of three states at any one particular time; they can either be a leader, a candidate, or a follower. When a node joins the cluster, it joins as a follower. The first thing it does is start a count down (called an election timeout) which lasts an arbitrary number of milliseconds. Each node controls how long its election timeout should last. If the election timeout expires before the leader of the cluster sends a message to it, the nodes starts an election.

To start an election, a node changes its state to candidate, it then increments its term by one, votes for itself, then sends a request to all of the nodes in the cluster asking for their vote.

When a node receives an election request from a candidate in the cluster, it evaluates whether it should vote for the candidate. One of the conditions it checks is whether the candidate’s term is greater than its own. It will only vote for the the candidate if this is true. If all the conditions are met, the node changes its term to that of the candidate then sends its vote back to the candidate.

When a candidate receives a vote from a node, it evaluates whether the total number of votes it has gotten so far in its current term is 50% of all nodes plus 1. If so, it sends out a request to all the nodes (including those that didn’t vote for it) indicating that it is now the leader for the term. Even after a leader is gotten or discovered, every follower and candidate continues to run their election timeout. They reset the timeout whenever they receive a message from the leader. This is done so that a node can be able to discover when the leader is unavailable so that it can start a new election to become the new leader.

Raft caters for not only the happy path, but also edge cases that might occur in leader election. The diagram on this slide shows the three node states and what makes a node transition from one of the states to another. The happy path is; that a node will start as a follower, its election timeout would expire, it would then change state to candidate then once it has received a majority of the votes, it changes state to leader.

However, if for instance, a candidate does not receive a majority of the votes before its election timeout expires, it restarts the election. Another edge case is when a node thinks its the leader then receives a message from a leader with a higher term, it changes its state back to follower.

I recommend you watching this section of my presentation for a visual explanation of how leader election works.

Log Replication

Log replication handles; how commands are gotten from the clients, sent to the nodes in the distributed system, and finally safely applied on their state machines.

It is, first, important to note that the leader is the only node allowed to receive commands from clients. This means that, either the clients should be aware which node is the current leader, or some mechanism should be built where if any of the followers receives a command from a client they proxy this command to the leader.

When a command is received by the leader, the leader will first append the command into its log. The leader will then forward the command to all the other nodes in the cluster. It does this using what is called an AppendEntries request. The AppendEntries request contains, apart from the command, the leader’s current term and metadata of the command in the leader’s log that appears right before the command sent in the request. The metadata for the previous log entry includes the index of the command in the log, and the term the command was received.

When a follower receives an AppendEntries request from the leader, it first checks whether its safe to append the command in the request into its own log Two of the checks done are; whether the follower’s term is the same as the leader’s term and, using the metadata in the AppendEntries request, whether what the leader indicated as the command saved in its log right before the command in the request also exists in the follower’s log (but as the last entry).

If the follower is able to insert the command to its log, it does so then sends back a response to the leader indicating that it has inserted the command into its log. When the leader receives back a majority positive responses from followers indicating the command was successfully inserted into their logs, it applies the command into its state machine, marks the command as committed in its log, then sends the state machine’s output back to the client.

The next AppendEntries request the leader sends to the followers will indicate that it has applied this command into its state machine. It is only then that the followers will also apply the command into their state machines. Raft uses this approach of first confirming that a majority of the nodes have a command in their log before applying the command in the state machines so that there is a general consensus of what the cluster expects the state machines should look like at any particular time. This is good because if the leader were to go down, you would want a majority of the rest of the nodes to know what the leader had likely applied to its state machine.

Note that the leader will send an AppendEntries request that doesn’t have any command to its followers as a form of heartbeat to assure the followers that it is still alive. It does this whenever the distributed system hasn’t received any command from its clients within a period of time. This time period is normally set to less than what is expected to be the election timeout in the nodes. Raft does this to prevent followers from starting an election because they didn’t receive any message from the leader before their election timeout expired.

I recommend you watching this section of my presentation for a visual explanation of how log replication works.

In the next post, I’ll explain how you can use distributed consensus to handle rolling software updates.