An SRE's Guide to Distributed Consensus, Part 3

This is the last of three posts on distributed consensus in the DevOps world. These posts are based on a presentation I gave to the Nairobi GNU/Linux Users Group. A video of the presentation can be found here.

The first post in this series introduced distributed consensus and the second post introduced the Raft consensus algorithm. In this post, I’ll present common DevOps problem and show how we can use distributed consensus to deal with this problem at scale.

Let’s say you need to manage the deployment of software updates to your infrastructure. Some of the requirements that you need to consider include:

- The software updates might be large. In some cases larger than 1GB.

- The software updates will be regular.

- The software updates should be deployed to the entire infrastructure quickly.

- The software updates should be done in a way that doesn’t cause service interruption.

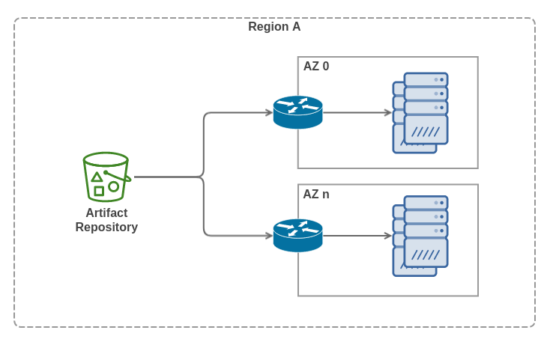

So you, initially, go with the approach where when a software update is published in your artifacts repository, an automated pipeline kicks in and begins the process of deploying the software update to your servers. The deployment pipeline targets tens of servers spread out across a few availability zones within the same geographic region. The deployment pipeline rolls an update to the servers by applying the update to a small chunk of the servers at a time. It takes tens of minutes to roll an update to your entire infrastructure.

There is no issue with each of the servers downloading the software updates from the centralized artifacts repository. Over time, however, your business grows and so does the need to have more servers in your fleet. You scale up your infrastructure to hundreds of servers spread out across different availability zones in different geographic regions. Some cracks in your deployment process begin to show:

- You notice that the artifacts repository is your biggest bottle-neck. The repository’s upload link speed limits how fast the software updates can be served to servers at the same time.

- You also notice that software updates take longer to download in availability zones that are geographically further from the region your artifacts repository is deployed in.

- Another thing you notice is that since your availability zones now have more servers in them than before, the availability zones’ downlinks become congested whenever the deployment pipeline kicks in because you now have more servers in the same availability zone trying to download the software update at the same time. Services deployed in your infrastructure experience reliability issues whenever a large software update is rolling because they aren’t able to fetch data from clients fast enough.

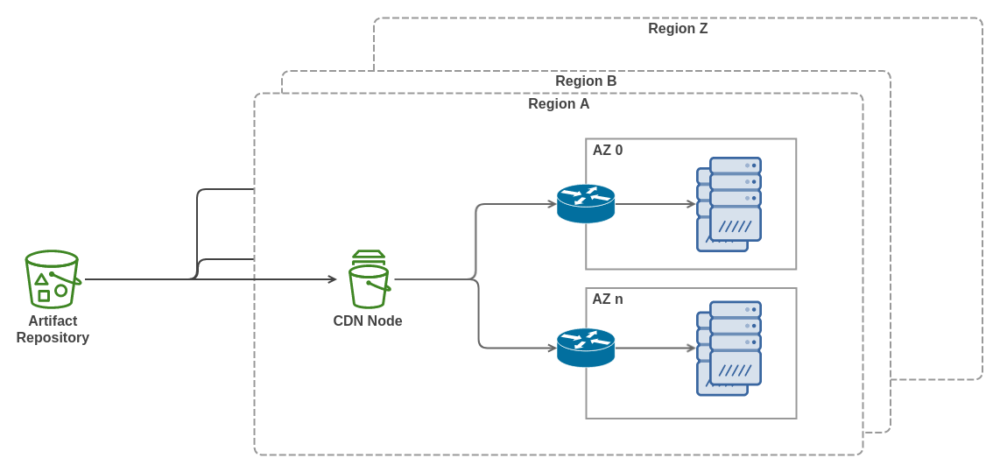

Scale Out Using CDNs

So, you decide to scale out your software release architecture. The updated architecture includes a CDN node running in each of the regions your infrastructure is deployed in.

When a software update is being rolled out to your infrastructure, the servers now download the software updates from the CDN node closest to them. The updated approach definitely works better. The downlinks in your availability zones, however, still get congested whenever a large software update is being deployed.

You scale your fleet to thousands of servers. Your software update process also starts becoming more complicated. For instance, because you now have to deal with far more advanced adversaries, you make it a requirement that a software update’s cryptographic signature has to be verified before the software update is applied to a server.

Also, since your fleet is now composed of different kinds of servers (let’s say Intel and AMD servers), you now have to confirm that an update was successfully deployed and is running okay for each of the kinds of servers you have deployed.

You notice that it is harder to coordinate the deployment process, centrally, from your Continuous Delivery tool, especially in cases where a deployment check has failed for a subset of your infrastructure and you need to rollback to the previous release for just this subset of servers. It’s harder because your centralized CD tool needs to get a status update from each of the thousands of servers as a deployment is running.

The CD tool also has to figure out which servers to rollback if a certain check fails on a server. For example, if the pre-flight checks pass on your first targeted Intel server but fail on your first targeted AMD server, it is safe to assume that it will fail on other AMD servers, so roll back the release on just the AMD server but continue the deployment on the Intel servers. This is just one of the permutations you have to deal with.

Distributed Consensus for Rolling Updates

How can distributed consensus help scale the deployment process further?

Here’s how I’d do it; I’d divide the servers into homogeneous groups. For instance, if the main distinguishing characteristics for servers in my fleet are the processor architecture and availability zone, then I’d have a group for each architecture in each availability zone. There would therefore be one group consisting of only Intel servers in availability zone A and another group for AMD servers in availability zone A. There would be a third group for Intel servers running in availability zone B and a forth group for AMD servers in availability zone B.

Each of these groups would coordinate the deployment process independently. For the group coordination to be reliable, I’d use a distributed consensus algorithm like Raft.

And… in order for me to use a distributed consensus algorithm like Raft to coordinate the software deployment process, I will need to represent the process as a state machine.

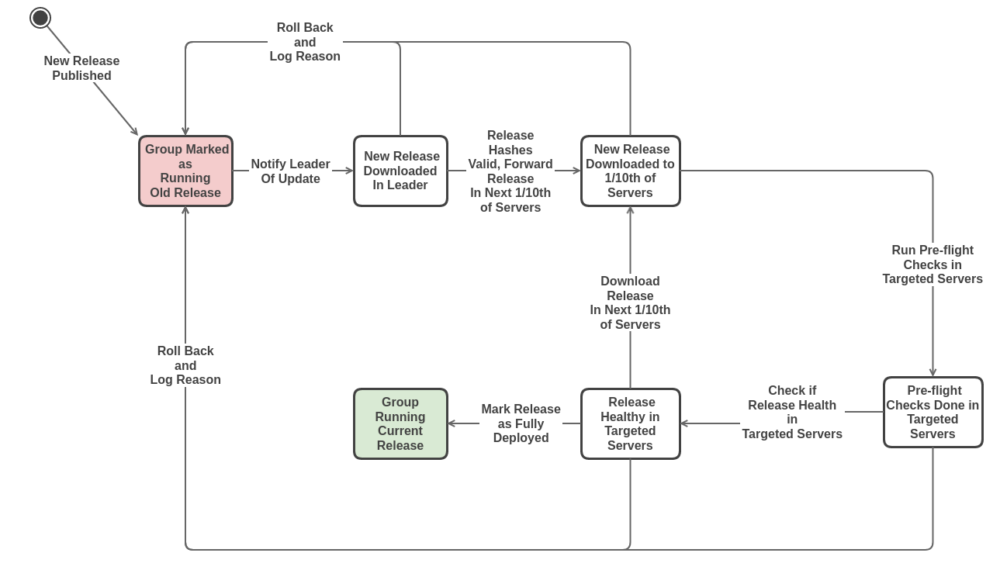

It turns out representing the software deployment process as a state machine isn’t too hard. The state machine diagram on this slide shows a hypothetical complex deployment process that involves cryptographic verification of an update, then rolling the release to 1/10th of the servers in a group at a time, and running pre-flight checks after the update is applied to a server.

If any of the steps fail, the group begins the process of rolling back to the previous software release. Now that the deployment process is represented as a state machine, how would the coordination actually work?

We’d have a software coordination service running in all the servers. The service would use Raft for distributed consensus. The servers in a group would elect a leader. The servers would also act as both the clients and servers in the group.

The leader, once elected, would be responsible for checking for software updates. When an update becomes available, it sends a command to the group of servers requesting for the state machine to change to the “Group Marked as Running Old Release” state. Once a majority of the servers in the group have this command in their log, the leader would go ahead and commit to the state by updating an infrastructure registry indicating that the group of servers is running an outdated version of the software.

The leader would then issue another command to transition from the “Group Marked as Running Old Release” state to the “New Release Downloaded in Leader” state. Once there’s a consensus from a majority of the servers that the group can transition to the state, the leader would commit to this by downloading the software update from the closest CDN node.

At this point the leader would cryptographically check whether the software update is valid and if so would issue another command to the group requesting that the group transitions to the “New Release Downloaded to the 1st 1/10th of Servers” state. When a consensus is reached the leader would proceed to commit to this by selecting the first 1/10th of the servers then requesting them to download the update.

Once all the selected 1/10th of servers all confirm that they have the software update downloaded, the leader would issue a command requesting the group to transition into the next state.

This kind of coordination would be done until a point where the group of servers is in the “Group Running Current Release” state or a rollback has been done and the group is back to the “Group Marked as Running Old Release” state and some form of intervention is needed.

If ever the leader were to go down during the software update process, there would be a graceful transition to another leader since a majority of the servers are aware of the current state of the deployment process. The new leader would just pick up from where the old leader left off.

There you have it. That’s how I’d use distributed consensus to run the software update process in a massively scaled set of servers.